Utilization Review Guidelines for Spinal Fusion and Smoking Cigarettes

- Inquiry

- Open Admission

- Published:

The impact of smoking on outcomes following anterior cervical fusion-nonfusion hybrid surgery: a retrospective unmarried-center cohort written report

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 22, Article number:612 (2021) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

There is mixed evidence for the bear on of cigarette smoking on outcomes following inductive cervical surgery. It has been reported to have a negative impact on healing after multilevel anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, however, segmental mobility has been suggested to be superior in smokers who underwent one- or two-level cervical disc replacement. Hybrid surgery, including anterior cervical discectomy and fusion and cervical disc replacement, has emerged every bit an alternative procedure for multilevel cervical degenerative disc affliction. This study aimed to examine the bear on of smoking on intermediate-term outcomes following hybrid surgery.

Methods

Radiographical and clinical outcomes of 153 patients who had undergone continuous two- or three-level hybrid surgery were followed-upwardly to a minimum of 2-years post-operatively. The early fusion effect, one-yr fusion rate, the incidence of bone loss and heterotopic ossification, as well as the clinical outcomes were compared across three smoking status groups: (1) current smokers; (2) one-time smokers; (3) nonsmokers.

Results

Clinical outcomes were comparable amid the 3 groups. Nonetheless, the electric current smoking group had a poorer early fusion effect and 1-year fusion rate (P < 0.001 and P < 0.035 respectively). Both gender and smoking status were considered as key factors for i-yr fusion rate. Upon multivariable analysis, male person gender (OR = 6.664, 95% CI: 1.248–35.581, P = 0.026) and current smoking status (OR = 0.009, 95% CI: 0.020–0.411, P = 0.002) were significantly associated with 1-year fusion charge per unit. A subgroup analysis demonstrated statistically pregnant differences in both early fusion procedure (P < 0.001) and the 1-year fusion rate (P = 0.006) across the 3 smoking status groups in female patients. Finally, non-smoking status appeared to be protective confronting bone loss (OR = 0.427, 95% CI: 0.192–0.947, P = 0.036), with these patients likely to take at least one course lower bone loss than current smokers.

Conclusions

Smoking is associated with poor outcomes following hybrid surgery for multilevel cervical disc disease. Current smokers had the poorest fusion rate and virtually bone loss, but no statistically meaning differences were seen in clinical outcomes across the iii groups.

Groundwork

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a traditional surgical procedure for the treatment of cervical degenerative disc disease (CDDD). Although satisfactory postoperative clinical outcomes have been reported from this process, non-fusion remains a concern. Previous literature suggests that the fusion rate may decrease with number of segments involved, the fusion charge per unit for three-level ACDF has been reported every bit low as 56% up to 37 months after surgery [1]. In addition, multilevel fusion surgery decreases the cervical range of motion (ROM), leading to more pressure across next levels. This may increase the risk of adjacent segmental degeneration (ASD). Cervical disc replacement (CDR) has therefore gained widespread popularity to preserve segmental mobility and mitigate against the run a risk of ASD. Still, to date, Mobi-C and Prestige-LP bogus cervical discs are approved for use only in double-level CDDD by the Food and Drug Administration, although iii-level CDR has been successfully performed, it is still considered an experimental treatment [2, 3]. Hybrid surgery (HS), which combines ACDF and CDR has been proposed to mitigate these concerns. The objective of HS is to tailor the optimal surgical procedures to each target level according to its degenerative status. As a result, several series have demonstrated that this is a prophylactic and effective surgical procedure for the treatment of multilevel CDDD [iv,5,6,vii].

Cigarette smoking is known to be associated with several health bug, including asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other debilitating atmospheric condition. Virtually 1 billion people will die from smoking-related issues during the twenty-kickoff century [8]. Smoking has also been demonstrated to worsen bone health, with an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures and delayed fracture healing in current smokers. A meta-analysis of 40,753 patients showed that smoking increases the adventure of hip fracture by xxx-forty% [9]. A 2nd meta-analysis of 59,232 patients reported a 25% increase in overall fractures and 84% increase in hip fractures in smokers compared with nonsmokers [ten]. Moreover, several studies have reported a myriad of deleterious effects of smoking on patients undergoing spine surgery including increased complications, lower fusion rates, poorer clinical outcomes, and decreased quality of life [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Hilibrand et al. monitored 190 patients over ii years and institute smoking to be associated with a significant negative outcome on healing and clinical recovery after multilevel cervical ACDF with autogenous interbody graft [17]. Contradictory to this, Tu et al. found that segmental mobility was marginally improved in smokers in patients with i- and two-level CDR than non-smokers [18]. Notwithstanding, the event of smoking on anterior cervical HS is unclear. The adverse effects of smoking on arthrodesis and the potential benefits in arthroplasty contradict ane another in the context of a hybrid approach.

In the present study, we aimed to explore the clinical impact of smoking status on fusion and bone loss in patients undergoing ii- and three-level HS. To date, this is the first written report to address this issue. We also hope to explore the impact of smoking on postoperative outcomes of HS to improve the evidence for implementation.

Method

Patient population

This retrospective study was conducted in according with the approval of our institutional review board. Consecutive patients who had undergone two- and three-level HS using the Prestige-LP artificial cervical disc (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) and Zippo-P device (Synthes GmbH Switzerland, Oberdorf, Switzerland) in our institution were included in this analysis. The inclusion criteria were equally follow: (1) radiological findings consistent with foramen stenosis, ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament, obvious osteophytes on 10-ray or CT scan or herniated nucleus pulposus on MRI; (2) symptomatic cervical myelopathy or radiculopathy or both; (3) failed conservative management for 6 weeks or more; (4) patient provided informed consent to undergo sequent HS. The exclusion criteria were every bit follows: (ane) less than 24 months of complete follow-up; (2) incomplete clinical and radiological data; (3) other indicators for cervical surgery such as spinal trauma, tumors, infection; (4) previous cervical spine surgery.

Surgical technique

The pick of either arthroplasty or arthrodesis during HS has strict indications. CDR was performed at levels without sagittal plane translation > 3 mm or sagittal plane angulation > xi°; without the ROM < 3°; without a disc pinnacle loss > 50%; and without facet joint degeneration, bridge osteophytes, or instability. ACDF was performed at the levels that did not meet the in a higher place criteria.

All operations were performed past the same senior spine surgeon. The patient was placed on the back with the neck in the neutral position. A standard right-side approach to the anterior cervical spine was adopted. After sufficient decompression of the entirety of the intervertebral space, CDR was performed before ACDF where indicated. A prothesis of the most suitable size was implanted into the intervertebral space, and the same artificial bone tissue was used in all the arthrodesis levels. Finally, C-arm fluoroscopy was used to confirm the appropriate position of the implants.

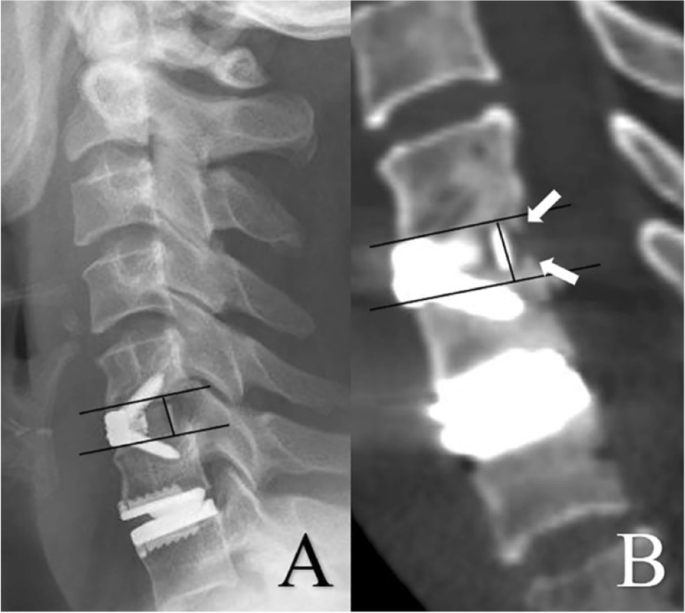

Clinical and radiological evaluations

Baseline demographics, clinical and radiological data were collected for all patients. Clinical outcomes were evaluated by the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) scale, Neck disability Alphabetize (NDI), and visual analog scale (VAS) for neck and arm pain both preoperatively and at the concluding follow-up appointment. Pre- and postoperative radiological evaluations included X-ray, CT, and MRI. Lateral and extension-flexion radiographs, sagittal reconstructed CT, and T2-weighted MRI were obtained at specified time points. Segmental ROM at the target level and the ROM of C2-seven was defined as the difference in the Cobb angle between extension and flexion radiographs. For patients with two-level CDR, the mean value of segmental ROM was used for further analysis. Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured at the L2-4 vertebral body. Heterotopic ossification (HO) was using the McAfee classification [xix] (Table 1). The classification of bone loss (BL) followed a validated methodology detailed in total elsewhere, based on a classification system reported by Saleh et al. in 2004 [twenty, 21] (Tabular array 2). For patients with 2-level CDR, the more astringent degree of HO and BL was recorded. McAfee grade III and IV HO were classified as high-grade HO. Early on fusion procedure was assessed using sagittal reconstructed CT scans at 3-month follow-up, measuring the height of new bone tissue at the posterior attribute of the cage (Fig. 1.) For patients with 2-level ACDF, the hateful value of new bone tissue was used for further analysis. The criteria to confirm fusion at 1-year were segmental ROM less than 3° in X-ray and continuous bone span demonstrated in CT imaging. For patients with two-level ACDF, if both levels had achieved fusion they were classified as "fusion", otherwise they were classified every bit "non-fusion". All measurements and ratings were completed by 2 independent spine surgeons, with corroboration by a third senior spine surgeon in example of disagreement.

A lateral 10-ray at 3-month follow-upwards was used to confirm the shape of endplates and the location of the marker line (A). The superlative of bone tissue along the posterior edge of the muzzle was measured in the sagittal CT scan as the reflection of early fusion effect. (The white arrows in B)

Study group and statistical analysis

The main explanatory variable for this report was smoking status. All patients were classified into 1 of three groups according to their smoking status at the fourth dimension of surgery: (ane) patients that had smoked cigarettes inside the twelvemonth prior to surgery were divers equally the electric current smokers; (2) patients with a smoking history but with cessation of smoking for more 1 year earlier surgery were defined as erstwhile smokers; (3) patients who had never smoked were defined as non-smokers. All patients were recommended to stop smoking postoperatively. Continuous variables were summarized using the mean boilerplate and standard deviation. Frequency data is presented as quantities and proportion. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS nineteen.0 for windows (IBM SPSS Inc, New York, United states). ANOVA analysis was used to compare continuous data across the three explanatory groups and Fisher'southward least significant divergence (LSD) exam was used for pairwise comparisons. Inter- and intra-observer reliability were assessed using intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to explore factors associated with bony fusion, and multiple ordered regression was used to identify the run a risk factors associated with BL. Both were presented as adapted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The alpha level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Baseline demographics

A total of 153 patients with complete clinical and radiological data were included in analyses. Of these, 51 (33.33%) were male and 102 (66.67%) were female. The mean age was 50.xi years old, with a mean follow-up of 40.82 months. In total, 79 patients underwent 2-level HS and 74 underwent iii-level HS. Other demographics information are summarized in Table 3.

Inter- and intra-observer differences

The inter- and intra-observer reliability were 0.94 and 0.91 for preoperative segmental ROM, 0.87 and 0.92 for preoperative C2-7 ROM, 0.92 and 0.96 for postoperative segmental ROM, 0.92 and 0.89 for postoperative C2-7 ROM, 0.98 and 0.97 for HO, 0.91 and 0.96 for bone loss, 0.95 and 0.91 for early fusion effect, 0.97 and 0.95 for ane-year fusion rate.

Smoking status

There were 40 (26.14%) current smokers, 34 (22.22%) former smokers and 79 (51.63%) non-smokers included in this report. Men were most likely to be current smokers while women were well-nigh likely to be nonsmokers (47.06% vs 66.67%, P < 0.001). The BMD value in the nonsmoking group was numerically higher than those of other 2 groups, but this was not statistically significant. The clinical and radiological outcomes by the signal of final follow-up were comparable across all three groups. No statistical differences were found in the incidence of HO and BL, just the electric current smoking group had the worst early fusion event (P < 0.001) and lowest 1-year fusion rate (P < 0.035) (Table 4) Upon multivariable analysis, both gender and smoking status were associated with one-year fusion rate (Fig. 2). Male patients (OR = 6.664, 95% CI: i.248–35.581, P = 0.026) displayed increased odds whilst non-smokers demonstrated reduced odds (OR = 0.009, 95% CI: 0.020–0.411, P = 0.002) (Tabular array 5). Subgroup analysis was therefore used to farther explore the consequence of gender and smoking status on the postoperative outcomes. Although there were significant differences in early fusion process among the 3 smoking status groups for male group (P < 0.001), no meaning differences were observed in 1-year fusion rate (Table 6). Yet, for female patients, statistical differences were plant in both early on fusion process (P < 0.001) and the 1-twelvemonth fusion rate (P = 0.006) (Table 7). Additionally, no pregnant differences were observed in the degree of HO amid the three smoking status groups, however, the degree of BL in current smokers was found to exist the most severe (P < 0.001) (Table 8). Reinforcing this, multiple ordered regression demonstrated that sex was not associated with BL, whilst smoking condition was significantly associated (Table nine). Current smokers demonstrated the well-nigh serious BL, and patients who had never smoked were probable to have at least one grade lower BL than current smokers (OR = 0.427, 95% CI: 0.192–0.947, P = 0.036).

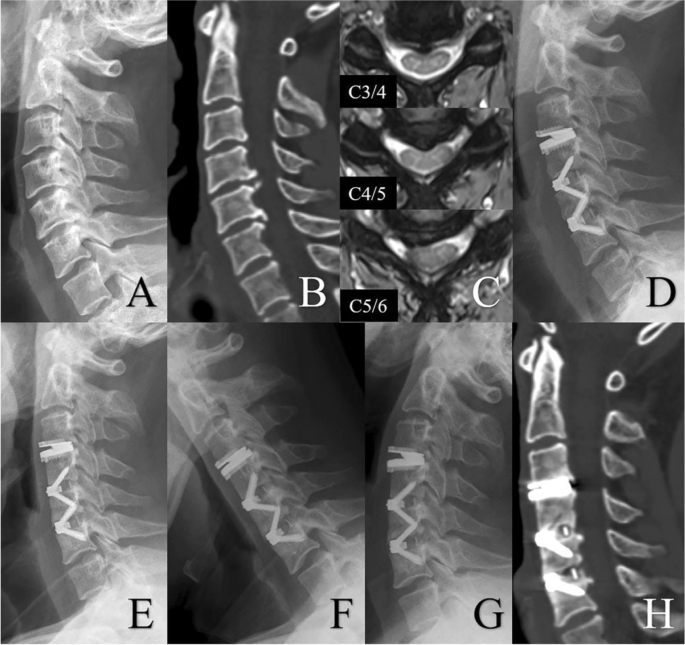

Radiologic examinations of a 45-yr older woman with cervix pain for 1 twelvemonth, who had cigarette consumption for more than 10 years. Preoperative lateral X-ray showed skillful cervical lordosis (A). Yet, a sagittal CT scan showed osteophytes at the posterior border of C4/five and C5/6 (B). MRI demonstrated spinal cord compression at C3/iv, C4/5 and C5/half-dozen (C). The patient underwent HS, including CDR at C3/4, and ACDF at C4/5 and C5/half-dozen (D). At 1-year follow-up, lateral Ten-ray shows satisfactory cervical lordosis (E), and extension-flexion view showed good cervical ROM (F and One thousand). However, a postoperative CT scan showed incomplete bony fusion at both two arthrodesis levels (H)

Give-and-take

HS, including both CDR and ACDF, is now ane of the nigh common surgical procedures for the treatment of patients with cervical spondylosis. Previous studies accept suggested that smoking may limit bony fusion following ACDF, but has a potential advantage in the ROM permitted after CDR. For the patients undergoing a hybrid approach, evidence is alien, with an unclear effect of smoking where both arthroplasty and arthrodesis are performed. To the all-time of our cognition, this is the outset written report that focuses on this issue, it aimed to explore the touch of smoking on clinical outcomes and complications later on HS.

The negative bear upon of smoking on os wellness has been well described, including increased rates of osteoporosis, osteoporotic fracture and bone loss. The Nurses' Wellness Report, a prospective cohort of 121,701 female nurses aged between 30–55 years sometime, plant that current smokers had a dose-contained increase in the incidence of hip fracture compared with non-smokers [22]. A Norwegian accomplice study of 34,856 adults aged more 50 years old showed smoking was associated with the incidence of the hip fracture in both sexes, and that effect was independent off trunk mass index and physical inactivity [23]. Additionally, a community-based, longitudinal, epidemiologic written report of osteoporosis in 1789 people over the age of 60 showed smoking was associated with 5–eight% lower BMD at the spine and the femoral neck [24]. The present study corroborated these findings, demonstrating that BMD was higher in the not-smokers than in electric current and former smokers. Our data suggest a degree of recovery of bone health in sometime smokers, with a mean BMD value between that of electric current and non-smokers. Even so, previous studies have reported that few differences in BMD was observed between current and former smokers [24, 25]. This warrants farther investigation in future piece of work.

In cervical spine arthrodesis, several studies have shown that smoking has a negative impact on healing following spinal fusion surgery [11, xv, 17]. This is supported by a considerable body of translational research devoted to exploring the mechanistic effects of smoking on os healing. Chang et al. reported that cigarette smoking impairs angiogenesis in early bone healing procedure and delays fracture union [26]. Ueng et al. hypothesized that smoking delays mineralization during the bone healing process and further decreases the mechanical strength of the regenerating os [27]. EI-Zawawy et al. found that smoking delays chondrogenesis during bone healing in a mouse model [28]. Supporting this, in our written report less new bone tissue was measured at the posterior margin of the muzzle in the current smokers, compared with the former and non-smokers. In farther laboratory piece of work, Davies et al. reported nicotine to have deleterious effects on wound healing through increased vasoconstriction [29]. Gaston et al. put forward several hypotheses virtually the bear upon of smoking on os healing procedure, including reduced blood supply, deficiency of vitamins and antioxidants, and high levels of reactive oxygen intermediates [xxx].

Gender is a potential misreckoning factor in this study, with a higher charge per unit of current smokers than non-smokers in male person patients, and a significantly higher fusion rate in male person compared with female patients. To explore the effect of smoking on the bony fusion, subgroup analyses were performed by gender. No significant differences were observed in male patients across smoking condition groups. For female patients in the current smoking group, a lower fusion charge per unit was observed than that of former smokers and nonsmokers. One reason for this may be related to estrogen levels. The average age of included patients was around 50 years old, which commonly represents the perimenopausal flow. A decrease in the circulating estrogen level may pb to a subtract in BMD and bony fusion. Additionally, it has been previously reported that smoking may lead to decreased bio-availability of estrogen in target tissues [31]. This may explain the reason why women in the current smoking group showed a poorer one-twelvemonth fusion rate. Although the reasons are probable to be multifactorial, our written report broadly confirms that smoking has a negative impact on os healing, and may impair early osteogenesis and fusion of arthrodesis levels in patients undergoing HS.

In terms of the outcome of smoking on the arthroplasty levels, however, current inquiry is very express. To date, only a single retrospective written report of 197 patients who underwent 1- or two-level CDR has been reported. At an boilerplate of 3.five years follow-upwards, Tu et al. reported similar clinical outcomes between current smokers and non-smokers, but with a slightly amend segmental ROM observed in smokers [18]. In the nowadays written report, no pregnant differences were institute in clinical outcomes or ROM across the three smoking status groups. Notwithstanding, the patients in the current smoking group had the highest level of BL among the three groups. Wang et al. performed a systematic review of six studies including 440 patients who underwent CDR across 536 segments. They found that patients with BL achieved similar clinical outcomes compared with those without BL [32]. Wu et al. performed a retrospective study of 396 patients in a single heart and found BL did non affect clinical outcomes but patients with BL had a larger segmental ROM [33]. Notwithstanding, Hacker et al. reported that i patient with BL had recurrent neck and arm pain for 52 months postoperatively, with radiological evaluations demonstrating segmental kyphosis. This patient eventually required revision surgery and ii-level ACDF [34]. Once more, a wealth of bones research has demonstrated the bear on of smoking on resorption and BL in animal models [35, 36]. Although the clinical outcomes associated with BL remain unclear, it should exist recognized that astringent BL can lead to prosthesis collapse, and a need for revision. Additionally, no meaning differences were observed in the incidence of HO amidst the three smoking groups, just with a trend towards more severe HO in current smokers. Although HO is essentially an osteogenic process, its true mechanism is still unclear. Male gender, old age and multilevel diseases accept been previously considered to be risk factors for HO [37, 38]. A meta-analysis of 94 studies indicated that the incidence of HO increased over time in studies with longer follow-up [39]. Another meta-analysis compared the incidence of high-form HO across studies and plant a significant variability between different prostheses [40]. Additionally, endplate coverage, segmental angle and center of rotation were all considered to be associated with the presence of HO [41,42,43]. However, the effect of smoking on HO requires farther exploration.

In summary, smoking had a negative touch on patients undergoing HS. The patients in the electric current smoking grouping had a worse early fusion process and 1-yr fusion rate, peculiarly in female person patients, every bit well every bit more serious BL. Smoking cessation is recommended for all patients before HS. Additionally, all patients undergoing HS are required to wear a collar for at least three months in our institution, with supervised activity permitted during the starting time three weeks postoperatively. Because the poor early fusion effect and stability in current smokers, protracted periods in a neck caryatid and reduced activity may exist necessary for these patients in the early postoperative period. The present study has some limitations. First, the retrospective design may have led to potential choice bias. The dose and elapsing of smoking were besides unavailable. Second, passive smoking history was non included as a factor in the multivariable models, which may have introduced unmeasured confounding. Third, the patient sample was small and the follow-upwards duration was short, with data merely from a single institution. A multicenter written report with a larger sample size and longer follow-up period would exist important to provide stronger prove.

Conclusion

This written report showed that smoking has a negative impact on the patients undergoing HS. Smoking cessation is of import to consider for these patients before surgery in society to reduce risk and approach baseline. The patients in the electric current smoking grouping had a worse early fusion effect and 1-year fusion charge per unit, besides as more serious BL. However, no meaning differences were observed in clinical outcomes amidst the iii groups.

Availability of information and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- ACDF:

-

Inductive cervical discectomy and fusion

- CDDD:

-

Cervical degenerative disc disease

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- ASD:

-

Adjacent segmental degeneration

- CDR:

-

Cervical disc replacement

- HS:

-

Hybrid surgery

- JOA:

-

Japanese Orthopaedic Association

- NDI:

-

Neck disability index

- VAS:

-

Visual analog calibration

- HO:

-

Heterotopic ossification

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- BL:

-

Bone loss

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

References

-

Emery SE, Fisher JR, Bohlman HH: Three-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: radiographic and clinical results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997, 22(22):2622–2624; give-and-take 2625.

-

Friesem T, Khan S, Rajesh M, Berg A, Reddy G, Bhatia C: Long Term Follow Up of Multi-Level (3 & Four Levels) Cervical Disc Arthroplasty—Results From a Single Heart %J. Spine J. 2017, 17(3).

-

Chang HK, Huang WC, Tu Thursday, Fay LY, Kuo CH, Chang CC, Wu CL, Lirng JF, Wu JC, Cheng H, et al. Radiological and clinical outcomes of three-level cervical disc arthroplasty. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;32(ii):174–81.

-

Wang H, Huang K, Liu H, Meng Y, Wang 10, Ding C, Hong Y. Is Cervical Disc Replacement Valuable in 3-Level Hybrid Surgery Compared with 3-Level Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion? World Neurosurg. 2021;146:e151–e160.

-

Wang H, Meng Y, Liu H, Wang 10, Ding C: A Comparison of 2 Anterior Hybrid Techniques for 3-Level Cervical Degenerative Disc Disease. Med Sci Monit 2020, 26:e927972.

-

Zhang J, Meng F, Ding Y, Li J, Han J, Zhang Ten, Dong W: Comprehensive Assay of Hybrid Surgery and Inductive Cervical Discectomy and Fusion in Cervical Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99(5):e19055.

-

Hollyer MA, Gill EC, Ayis S, Demetriades AK. The prophylactic and efficacy of hybrid surgery for multilevel cervical degenerative disc illness versus inductive cervical discectomy and fusion or cervical disc arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2020;162(2):289–303.

-

Wipfli H, Samet JM. Global economic and health benefits of tobacco control: part 1. Clin Pharmacol Therapeutics. 2009;86(iii):263–71.

-

Ward KD, Klesges RC. A meta-analysis of the effects of cigarette smoking on os mineral density. Calcified Tissue Int. 2001;68(5):259–70.

-

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, McCloskey EV, Mellstrom D, et al. Smoking and fracture adventure: a meta-analysis. Osteoporosis Int. 2005;16(2):155–62.

-

Andersen T, Christensen FB, Laursen G, Høy Thousand, Hansen ES, Bünger C: Smoking as a predictor of negative outcome in lumbar spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001, 26(23):2623–2628.

-

Bisson EF, Bowers CA, Hohmann SF, Schmidt MH. Smoking is Associated with Poorer Quality-Based Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Spinal Illness. Front Surg. 2015;2:twenty.

-

De la Garza Ramos R, Goodwin CR, Qadi One thousand, Abu-Bonsrah Northward, Passias PG, Lafage Five, Schwab F, Sciubba DM: Affect of Smoking on 30-twenty-four hours Morbidity and Mortality in Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017, 42(7):465–470.

-

Elsamadicy AA, Adogwa O, Sergesketter A, Vuong VD, Lydon E, Behrens S, Cheng J, Bagley CA, Karikari IO. Reduced Impact of Smoking Status on 30-Twenty-four hours Complication and Readmission Rates After Elective Spinal Fusion (≥3 Levels) for Developed Spine Deformity: A Single Institutional Report of 839 Patients. World Neurosurg. 2017;107:233–viii.

-

Hermann PC, Webler M, Bornemann R, Jansen TR, Rommelspacher Y, Sander Thou, Roessler PP, Frey SP, Pflugmacher R. Influence of smoking on spinal fusion afterward spondylodesis surgery: A comparative clinical report. Technol Health Care. 2016;24(5):737–44.

-

Seicean A, Seicean South, Alan Due north, Schiltz NK, Rosenbaum BP, Jones PK, Neuhauser D, Kattan MW, Weil RJ: Consequence of smoking on the perioperative outcomes of patients who undergo elective spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013, 38(15):1294–1302.

-

Hilibrand AS, Fye MA, Emery SE, Palumbo MA, Bohlman HH. Impact of smoking on the issue of anterior cervical arthrodesis with interbody or strut-grafting. J Bone joint Surg Am. 2001;83(5):668–73.

-

Tu Th, Kuo CH, Huang WC, Fay LY, Cheng H, Wu JC. Effects of smoking on cervical disc arthroplasty. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;30(2):168–74.

-

McAfee PC, Cunningham BW, Devine J, Williams Due east, Yu-Yahiro J. Nomenclature of heterotopic ossification (HO) in artificial deejay replacement. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;sixteen(four):384–ix.

-

He J, Liu H, Wu T, Ding C, Huang One thousand, Hong Y, Wang B. Association between anterior bone loss and anterior heterotopic ossification in hybrid surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(i):664.

-

Saleh KJ, Thongtrangan I, Schwarz EM. Osteolysis: medical and surgical approaches. Clin Orthopaedics Related Res. 2004;427:138–47.

-

Cornuz J, Feskanich D, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Smoking, smoking cessation, and risk of hip fracture in women. Am J Medicine. 1999;106(3):311–four.

-

Forsén Fifty, Bjørndal A, Bjartveit K, Edna Thursday, Holmen J, Jessen 5, Westberg G. Interaction between current smoking, leanness, and physical inactivity in the prediction of hip fracture. J Bone Mineral Res. 1994;9(11):1671–8.

-

Nguyen TV, Kelly PJ, Sambrook PN, Gilbert C, Pocock NA, Eisman JA. Lifestyle factors and bone density in the elderly: implications for osteoporosis prevention. J Os Mineral Res. 1994;ix(ix):1339–46.

-

Szulc P, Garnero P, Claustrat B, Marchand F, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD. Increased bone resorption in moderate smokers with depression body weight: the Minos study. The J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):666–74.

-

Chang CJ, Jou IM, Wu TT, Su FC, Tai TW. Cigarette fume inhalation impairs angiogenesis in early os healing processes and delays fracture wedlock. Os Joint Res. 2020;9(3):99–107.

-

Ueng SW, Lin SS, Wang CR, Liu SJ, Tai CL, Shih CH. Bone healing of tibial lengthening is delayed by cigarette smoking: written report of bone mineral density and torsional strength on rabbits. JTrauma. 1999;46(1):110–5.

-

El-Zawawy HB, Gill CS, Wright RW, Sandell LJ. Smoking delays chondrogenesis in a mouse model of closed tibial fracture healing. J Orthopaedic Res. 2006;24(12):2150–viii.

-

Davies CS, Ismail A: Nicotine has deleterious furnishings on wound healing through increased vasoconstriction. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2016, 353:i2709.

-

Gaston MS, Simpson AH. Inhibition of fracture healing. J Bone Joint Surg Brit . 2007;89(12):1553–60.

-

Michnovicz JJ, Hershcopf RJ, Naganuma H, Bradlow HL, Fishman J. Increased ii-hydroxylation of estradiol as a possible machinery for the anti-estrogenic effect of cigarette smoking. New England J Med. 1986;315(21):1305–ix.

-

Wang XF, Meng Y, Liu H, Hong Y, Wang Past. Anterior bone loss after cervical disc replacement: A systematic review. Earth J Clin Cases. 2020;eight(21):5284–95.

-

Wu TK, Liu H, Wang BY, He JB, Ding C, Rong Ten, Yang Y, Huang KK, Hong Y. Incidence of bone loss afterward Prestige-LP cervical disc arthroplasty: a single-center retrospective written report of 396 cases. Spine J. 2020;20(8):1219–28.

-

Hacker FM, Babcock RM, Hacker RJ: Very late complications of cervical arthroplasty: results of 2 controlled randomized prospective studies from a unmarried investigator site. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013, 38(26):2223–2226.

-

Xu J, Qiu X, Liang Z, Smiley-Jewell S, Lu F, Yu Yard, Pinkerton KE, Zhao D, Shi B. Exposure to tobacco smoke increases bone loss in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Inhalation Toxicol. 2018;30(6):229–38.

-

Moretto Nunes CM, Bernardo DV, Ferreira CL, Gomes MF, De Marco Air-conditioning, Santamaria MP, Jardini MAN. Influence of Cigarette Smoke Inhalation on an Autogenous Onlay Bone Graft Area in Rats with Estrogen Deficiency: A Histomorphometric and Immunohistochemistry Report. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; xx(8):1854.

-

Nunley PD, Cavanaugh DA, Kerr EJ 3rd, Utter PA, Campbell PG, Frank KA, Marshall KE, Stone MB. Heterotopic Ossification Later Cervical Full Disc Replacement at seven Years-Prevalence, Progression, Clinical Implications, and Run a risk Factors. Int J Spine Surg. 2018;12(3):352–61.

-

Jin YJ, Park SB, Kim MJ, Kim KJ, Kim HJ. An analysis of heterotopic ossification in cervical disc arthroplasty: a novel morphologic classification of an ossified mass. Spine J. 2013;xiii(4):408–20.

-

Hui Northward, Phan Chiliad, Kerferd J, Lee Grand, Mobbs RJ. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Heterotopic Ossification After Cervical Full Disc Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Global Spine J. 2020;10(half dozen):790–804.

-

Wahood Westward, Yolcu YU, Kerezoudis P, Goyal A, Alvi MA, Freedman BA, Bydon M. Artificial Discs in Cervical Disc Replacement: A Meta-Assay for Comparing of Long-Term Outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2020;134:598-613.e595.

-

Zeng J, Liu H, Chen H, Rong X, Meng Y, Yang Y, Deng Y, Ding C: Consequence of Prosthesis Width and Depth on Heterotopic Ossification After Cervical Disc Arthroplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019, 44(9):624–628.

-

Hu Fifty, Zhang J, Liu H, Meng Y, Yang Y, Li K, Ding C, Wang B. Heterotopic ossification is related to modify in disc space angle after Prestige-LP cervical disc arthroplasty. Eur Spine J. 2019;28(ten):2359–70.

-

Suchomel P, Jurák L, Antinheimo J, Pohjola J, Stulik J, Meisel HJ, Čabraja Grand, Woiciechowsky C, Bruchmann B, Shackleford I, et al. Does sagittal position of the CTDR-related centre of rotation influence functional upshot? Prospective 2-year follow-up assay. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(5):1124–34.

Acknowledgements

Not applicative.

Funding

This written report was supported by the ane.3.five Project for Disciplines of Excellence (ZYJC18029), the Mail-Doctor Inquiry Project (2018HXBH002), and the W Mainland china Nursing Subject field Development Special Fund Project (HXHL19016) of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. and Y.M. analyzed and interpreted all data, performed statistical analysis and prepared the manuscript. Collection and analysis of radiographs were performed by Y.H. and 10.Westward.. H.L. designed and supervised the study. All authors accept read and approved the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approving and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University, and follows the ideals principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 1964, and the informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this written report. The authors declare that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long equally you lot requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd political party material in this article are included in the article'due south Creative Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article'southward Artistic Eatables licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Meng, Y., Liu, H. et al. The bear upon of smoking on outcomes following anterior cervical fusion-nonfusion hybrid surgery: a retrospective single-center cohort report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 612 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04501-four

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04501-four

Keywords

- Cervical disc replacement

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion

- Hybrid surgery

- Heterotopic ossification

- Bone loss

- Smoking

Source: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-021-04501-4